Shamsi Iqbal, a principal researcher in the Productivity and Intelligence Group at Microsoft Research, says she was nervous before she was about to introduce a keynote speaker to some 200 people in a video meeting. But she was also prepared.

Before settling down in her home office that day, she had put up signs all over her house in Seattle, warning her husband and children that she would be on an important call until 11 a.m. and couldn’t be interrupted—no matter what.

Still, when the time arrived and all eyes were on her, Iqbal’s 7-year-old son poked his head in her office and asked, “Can I be a Dementor for Halloween?”

Facepalm.

Iqbal kept her cool and finished the introduction without missing a beat. But it later occurred to her that her son’s question about the soul-sucking Harry Potter demon wasn’t all that different from the countless digital notifications she receives, each arriving without any consideration of her state of mind or busyness at that minute.

And, like a 7-year-old interrupting your carefully planned speech, that can be a problem. Potentially a big one.

As it happens, that’s the crux of Iqbal’s research: finding ways for employees to balance focus and flow with the distractions—digital and otherwise—that seek to take them off task, costing businesses both time and money. Her work is on the front lines in the battle against distraction, which only seems to grow year after year, thanks to new digital tools and an increasing societal expectation that our communications be synchronous—that is, that we respond in real time, all the time.

“In many cases, I don’t think you can necessarily avoid distraction,” she admits. “But I think you can prepare yourself better for dealing with it.”

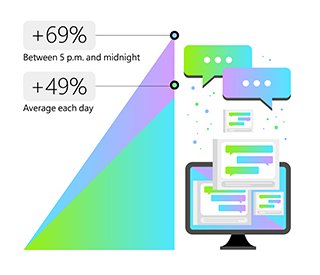

Since the pandemic, people are sending an average of 49 percent more Teams chats per person each day. This number jumps to a 69 percent increase for chats between 5 p.m. and midnight.

Illustration by Valerio Pellegrini

Source: Microsoft Work Trend Index

Here’s the thing about distractions: They aren’t just the brief, discrete events that they seem. Iqbal has discovered that an initial distraction often leads to a series of behaviors that take employees away from the task at hand for as long as 25 minutes at a time.

On-Off Button

Productivity researchers like Iqbal have identified three flavors of workplace distraction: digital, in person, and internal. Each type requires its own strategies to combat it.

In many ways, digital distractions are the most common—and annoying—but also the easiest to counteract. After all, some are simply automated notifications, letting you know that you have a new email in your inbox or a message waiting for you in Microsoft Teams.

The solution to managing these distractions is often to just turn them off. But Iqbal and other productivity researchers have developed more nuanced strategies to manage them, and Microsoft has developed far more sophisticated tools than a simple on-off button.

Windows 10, for example, introduced Focus Assist , a tool that allows users to turn on specific kinds of notifications, like alarms or priority messages, but leave off others. You can also create plans that help you set up regular time to focus each week before your calendar fills up. If you’re a MyAnalytics customer, use the MyAnalytics Outlook add-in to book focus time in your calendar. When you’re in your focus time, your Teams status will change to “Focusing” and all notifications will be silenced until your focus time ends.

How does this play out in practice?

Zach Beardslee, senior integration architect at Cerner, a health-care IT company, says MyAnalytics helped him figure out how to find opportunities to focus in a “meeting-heavy” work culture.

“It’s really changed my perspective on my work ethic and showed me areas where I can improve, such as not scheduling back-to-back meetings or asking myself, ‘Does this meeting really need to take an hour?’” he says.

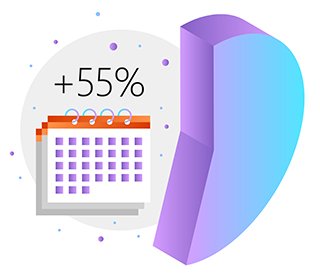

Since the pandemic started, people have 55 percent more meetings on their calendars each week.

Illustration by Valerio Pellegrini

Source: Microsoft Work Trend Index

In the future, Iqbal says, Microsoft could develop tools that might allow you to only receive notifications about critical emails from a coworker but not from a family friend who wants to plan a dinner.

But turning off your email notifications doesn’t exactly help if you keep your email application open while working on something else and constantly glance at the number of messages currently in your inbox. That’s why many productivity researchers recommend quitting your email and messaging apps unless you’re actively using them in the moment.

The second kind of distraction workers face is in person—typically other employees who want to talk to them. During the pandemic, such distractions have often been easier to avoid: with so many working from home, in-person interruptions from coworkers aren’t really a problem. At the same time, your colleagues can’t look over at your desk and see your nose buried in a report, which means you’re more likely to get inundated with pings and meeting invitations to make up for the lack of in-person access.

But Iqbal has found a simple hack to ensure that there are opportunities to focus throughout the day: scheduling, on your publicly accessible calendar, blocks of time when you’re unavailable for meetings, discussions, or anything else. Blocking out time for yourself to focus might not stop a 7-year-old. But communicating to your colleagues when to avoid interrupting you is a crucial tool for achieving focus, especially when they can’t physically see if you’re busy. For managers, setting aside focus time for themselves also has a ripple effect by creating a cultural norm for the whole team: “We prioritize focus. You can—and should—set aside time for yourself to focus, too.”

Inner Focus

The last kind of distraction is internal for the employee, which might be the hardest to battle.

Focusing on a task takes effort and concentration. That concentration drains your mental resources. Eventually, you’re going to need to take a mental break. And mental breaks often present themselves as distractions, like checking your LinkedIn feed or scrolling through Twitter.

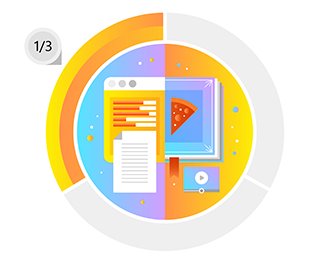

One-third of remote workers say the lack of separation between work and personal life is negatively impacting their wellbeing.

Illustration by Valerio Pellegrini

Source: Microsoft Work Trend Index

It’s tempting to think that blocking access to non-work-related sites would eliminate this sort of behavior—and indeed it does, but only for the most impulsive employees. For more conscientious employees who can block out distractions, Iqbal and her colleagues discovered that prohibiting access to non-work sites actually decreases productivity and increases stress in the long run, because they can’t take a break and return to “emotional homeostasis”—the state of re-energized evenness that lets you dive back into a task.

In fact, a colleague of Iqbal, Gloria Mark, a professor in the Department of Informatics at the University of California, Irvine, reports that workers, on average, switch tasks every three minutes and that they “are just as likely to interrupt themselves as to be interrupted by an external source.”

That’s why Iqbal says it’s not useful to think about your workday as just a series of tasks that need to get done. She says it’s vital to arrange your day in such a way that you have built-in mental breaks that give you time to rest and recharge.

Going forward, Iqbal says productivity research will focus more on helping employees take effective breaks from work so they can ultimately sustain their productivity over longer periods of time. (See, for example, the Headspace integration that makes it easy to schedule meditation breaks right in Teams.)

In other words, she’s going to be looking for ways to make distractions work for employers instead of against them.

“Our tools need to be broader,” she says. “Their focus should not be only about getting people to work more efficiently; it should also be about helping people be more resilient by incorporating their wellbeing needs during their workday.”

Prioritizing wellbeing might require a change in mindset. “More breaks” may sound like “less productive.” But wellbeing is a crucial part of achieving focus. And it’s in those periods of focus and flow, free competing demands on attention, that people get their best work done.